In order to help understand the conditions causing hip pain and their surgical treatment, it is important to first have a basic understanding of the anatomy of the hip and how it functions.

The hip joint is the largest weight-bearing joint in the human body. It is referred to as a ball and socket joint, and is surrounded by muscles, ligaments, and tendons. The thigh bone (femur) and the pelvis join to form the hip joint.

Any injury or disease of the hip or it’s surrounding structures will adversely affect the joint's range of motion, function, and ability to bear weight.

The hip joint is made up of the following:

- Bones and joints

- Ligaments and joint capsule

- Muscles and tendons

- Nerves and blood vessels that supply the bones and muscles of the hip

Bones and Joints

The hip joint is the junction where the hip joins the leg to the pelvis and trunk. It is comprised of two bones: the thigh bone (or femur) and the pelvis, which is made up of three fused bone segments called the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The ball of the hip joint is made by the femoral head, while the socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is a deep, circular socket formed on the outer edge of the pelvis. The stability of the hip is provided by the joint capsule of the acetabulum and the muscles and ligaments that surround and support the hip joint.

The surfaces of the head of the femur and the socket (acetabulum) are covered by articular (hyaline) cartilage (a very smooth substance that allows the bones to move against each other with minimal friction). Articular cartilage is the thin, tough, flexible, and slippery surface lubricated by synovial fluid that covers the weight-bearing bones of the body. It enables smooth movements of the bones and reduces friction. The femoral head rotates and glides within the acetabulum. A fibrocartilaginous lining called the labrum is attached to the acetabulum at it’s margin, and it further increases the depth and conformity of the socket.

The femur or thigh bone is one of the longest bones in the human body. The upper part of the femur consists of the femoral head, femoral neck, and greater and lesser trochanters. The head of the femur joins the pelvis (acetabulum) to form the hip joint. Next to the femoral neck, there are two protrusions known as greater and lesser trochanters that serve as sites of muscle attachment.

howtorelief.com

Ligaments

Ligaments are fibrous structures that connect bones to other bones. The hip joint is encircled with ligaments to provide stability to the hip by forming a dense and fibrous structure around the joint capsule. The ligaments adjoining the hip joint include:

- Iliofemoral ligament – This is the strongest of the capsular ligaments. It is a Y-shaped ligament that connects the pelvis to the femoral neck at the front of the joint. It helps in limiting over-extension of the hip.

- Pubofemoral ligament – This is a triangular shaped ligament that extends from the upper portion of the pubis to the iliofemoral ligament and capsule at the inferior neck region.

- Ischiofemoral ligament – This is the weakest of the 3 capsule-associated ligaments. It arises from the ischium behind the acetabulum and merges with the fibres of the joint capsule.

- Ligamentum teres – This is a small ligament that extends from a depression (fovea) in the tip of the femoral head and runs to the acetabulum. Although it has no role in hip movement, it does have a small artery within that supplies blood to a part of the femoral head.

- Acetabular labrum – The labrum is a fibrocartilaginous ring which attaches to the acetabular bony rim and encloses the femoral head beyond it’s equator. It deepens the cavity, increasing the stability and strength of the hip joint. It continues across the inferior acetabular notch as the transverse acetabular ligament.

pinterest.com

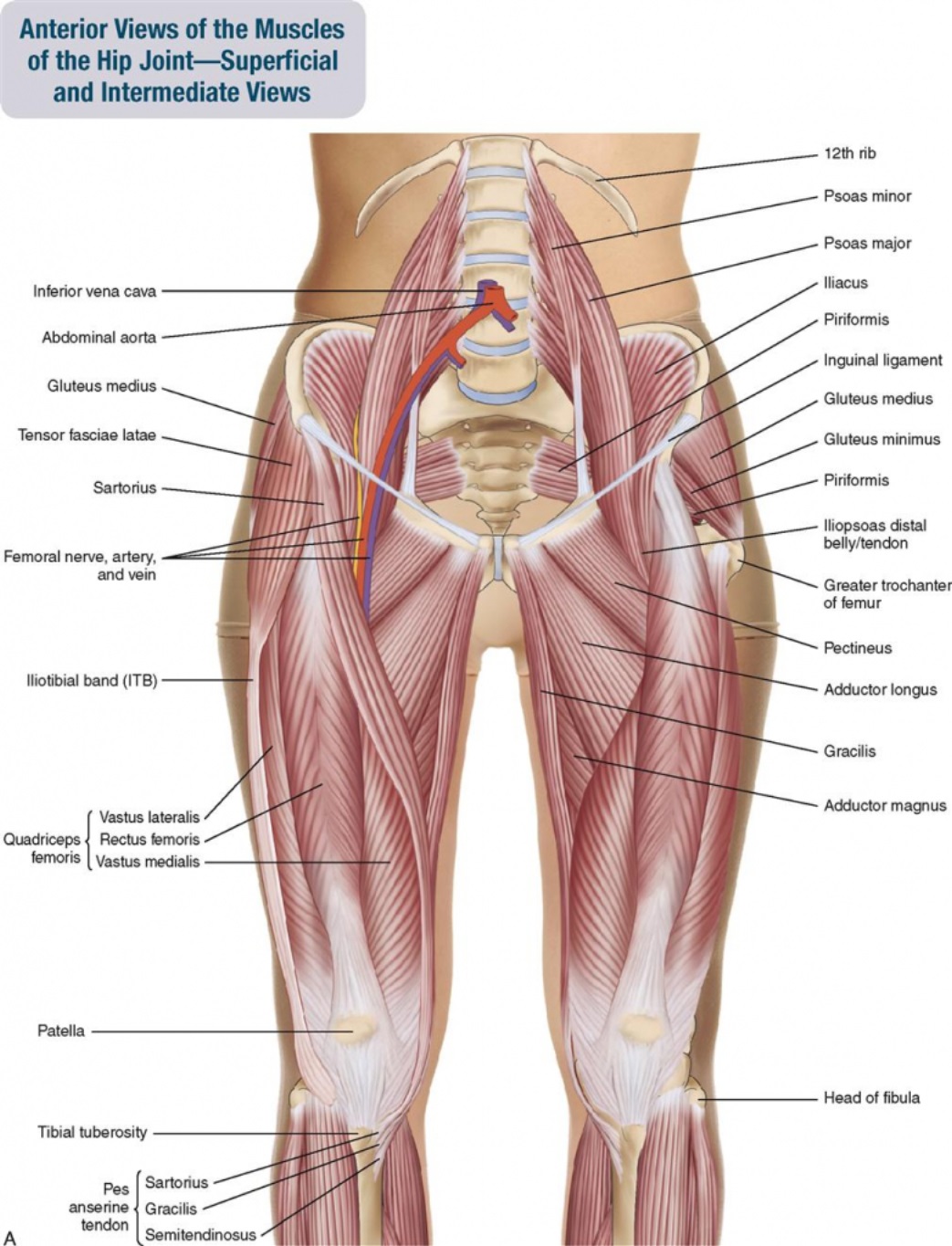

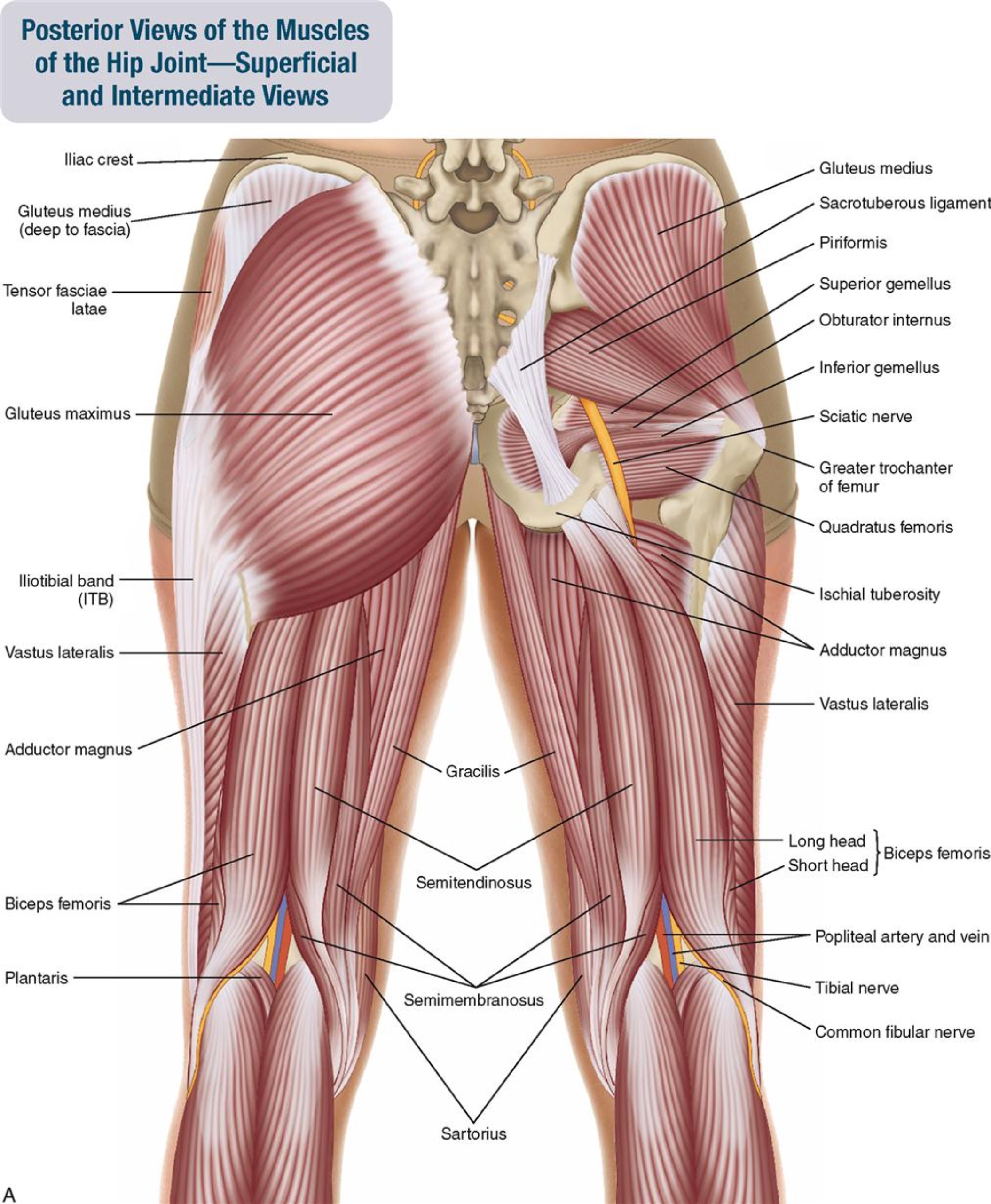

Muscles and Tendons

The muscles of the region are the three gluteal muscles, the deeper-placed piriformis, and short external rotator group, the adductor group of muscles, iliopsoas, rectus femoris and the rest of the quadriceps muscles, and the posterior situated hamstrings:

- Gluteals – These are the muscles that form the buttocks. There are three muscles (gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus) that attach to the back of the pelvis and insert into the greater trochanter of the femur, with some having attachments more distally to the femur and to the iliotibial band.

- Adductors – These muscles are located in the medial (inner) thigh which helps in adduction, the action of pulling the leg back towards the midline.

- Iliopsoas - This muscle is located in front of the hip joint and provides flexion. It is a deep muscle that originates from the lower back and pelvis, and extends up to the inside surface of the upper part of the femur at the lesser trochanter.

- Rectus femoris and Vastus muscles (Quads) – This is the largest band of muscles located in front of the thigh. They also are hip flexors.

- Hamstring muscles - These begin at the bottom of the pelvis (iscium) and run down the back of the thigh. Because they cross the back of the hip joint, they help in extension of the hip by pulling it backwards.

innerorgan.com

Musculoskeletalkey.com

Nerves and arteries

Nerves of the hip transfer signals from the brain to the muscles to aid in hip movement. They also carry the sensory signals such as touch, pain, and temperature back to the brain.

The main nerves in the hip region include the femoral nerve at the front of the hip, and the sciatic nerve at the back. The hip is also supplied by a smaller nerve known as the obturator nerve.

In addition to these nerves, there are blood vessels that supply blood to the lower limbs. The femoral artery, one of the larger arteries in the body, arises deep in the pelvis as the continuation of the iliac artery, and can be felt in front of the upper hip/thigh.

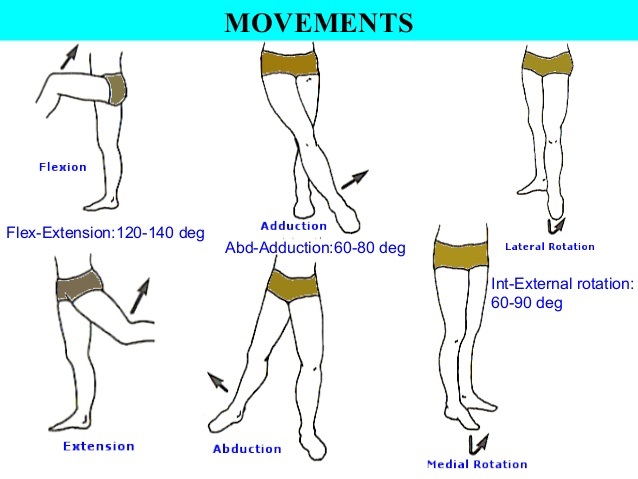

Hip movements

All of the anatomical parts of the hip work together to enable various hip movements. Hip movements include flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, circumduction, and hip rotation.