There are a number of systemic and/or aetiologic factors that may contribute to sacroiliac joint related pain. Therefore, a thorough history of clinical symptoms and a general medical history are important in all patients with suspected sacroiliac dysfunction.

Sacroiliac joint related pathologies include:

- Pregnancy and childbirth

- Trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents, fall onto the buttocks, repetitive lifting or twisting

- Inflammatory disease, such as ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis

- Iatrogenic – due to unsuspected damage during other lumbar or pelvic surgical procedures, such as bone graft harvesting

- Following lumbar spinal fusion – adjacent segment disorder/overload

- Secondary to long-standing scoliosis or leg-length discrepancy

signus.com

HISTORY

Symptoms related to sacroiliac dysfunction are similar to those reported with lumbar spine disc disease and hip pathologies. As with most conditions, diagnosis requires a thorough history and physical examination.

Most patients with sacroiliac dysfunction report pain that can be felt in a number of locations, and these include the buttock, lower lumbar region, medial groin and upper medial thigh, lateral hip region over the greater trochanter, the lower lateral thigh along the line of the iliotibial band, and sometimes to the medial (inner) distal calf, ankle and foot. Pain is typically worse with prolonged sitting and standing, but may even be reported when in bed, especially when lying on your side. When seated, patients will often shuffle about with difficulty finding a comfortable position. Hip rotation, especially external rotation of the leg into a “clam” position will often exacerbate symptoms. “Clunking” (more so than “clicking”) can be noted by many patients, along with a variable limp. Some neurological features are seen, especially paraesthesia (“pins and needles” sensation or tingling) in the distribution of the L5 nerve (which supplies the medial ankle and foot) – this is due to the close anatomic relationship of the L5 nerve which lies approximately 12mm over and in front of the sacroiliac joint before exiting the pelvis as part of the sciatic nerve. Dyspareunia (painful intercourse) is often reported by female patients. Female patients will often give a classical history of pain during the pregnancy, difficult or prolonged labour, large babies at childbirth, and delivery which resulted in tears or required episiotomy.

In longer standing cases of sacroiliac dysfunction, especially if there is a clear instability pattern demonstrated on Xrays, secondary degeneration and tearing can occur in a number of tendons that attach to the pelvis, particularly the hamstrings (at the ischial origin in the buttock), the abductor tendons (at the insertion to the greater trochanter (bony prominence at the top of the femur), and the adductor tendons (at the insertion to the inner groin). Mechanically, this is thought to result from overload to the tendons which are having to function as secondary “dynamic” stabilisers of the pelvis.

The average delay or time to diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction is in the region of 8 years! Not surprisingly, many patients who have suffered with debilitating chronic pain often report secondary depression. This is due to difficulties in obtaining a diagnosis, when often the patient has been “written off” and said to have a psychosomatic or psychological condition. Many patients have also had a multitude of other interventional procedures undertaken that fail to relieve the pain, including spinal surgery (bearing in mind that lumbar fusion increases the forces in the sacroiliac joint and may lead to degeneration in isolation), insertion of spinal stimulators or boxes, hip surgery (arthroscopy or arthroplasty), hernia procedures, or urological/gynaecological procedures. Multiple medications may have been prescribed over a long period, which may have led to narcotic (opioid) dependence and or other substance abuse, especially alcohol.

Unfortunately, one of the most troublesome issues with diagnosis appears to be the reluctance of many specialist clinicians (physicians and surgeons) to accept that sacroiliac dysfunction is a real condition in it’s own right. It seems that it is often easier for some doctors to perform a more common lumbar spine fusion or hip surgery rather than even consider sacroiliac pathology, and patient’s have reported that when these procedures have failed to relieve the initial presenting complaint, they are told that the doctor cannot do anything more for them, and they are usually sent for chronic pain team assessment at that stage.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination of any patient suspected of having sacroiliac dysfunction begins with assessment of the gait (walking) pattern, evidence of wasting of muscles in the buttocks or lower limbs, and thorough evaluation of the lumbar spine and hips to rule out secondary causes of pain, including peripheral neurological examination and ranges of motion.

Specifically, often patients can very accurately isolate an area of point tenderness at the posterior buttock region (known as the Fortin finger test). Multiple other areas of tenderness are also noted on palpation during examination including the medial groin (at the area where the 2 sides of the pelvis meet at the pubic symphysis), the adductor tendon insertion and over the proximal adductor tendons (on the upper medial thigh), over the greater trochanter region (bony prominence of the upper end of the femur), over the abductor tendon insertion to the greater trochanter, over the iliac crest (the bony prominence of the upper pelvis, and over the mid to lower lateral thigh along the line of the iliotibial band. Occasional hamstring insertion tenderness at the ischium (bony prominence at the inferior part of the pelvis0 can also be found.

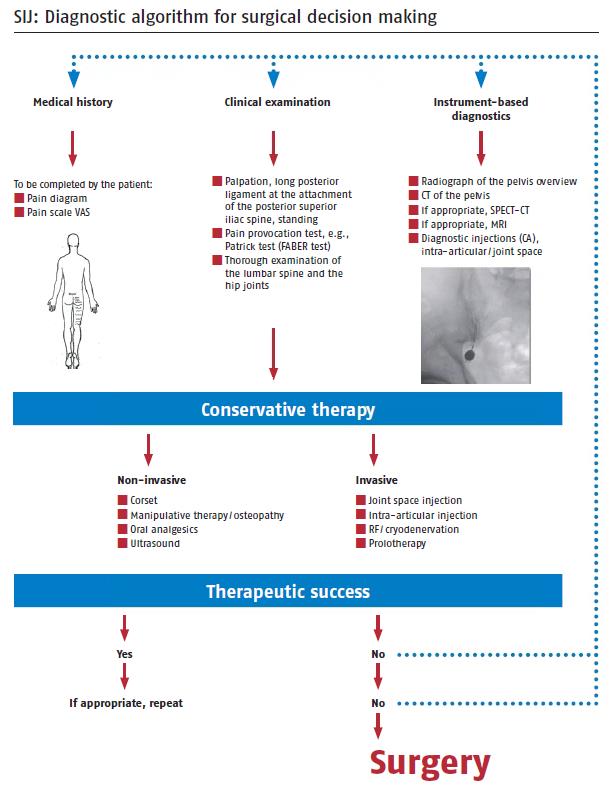

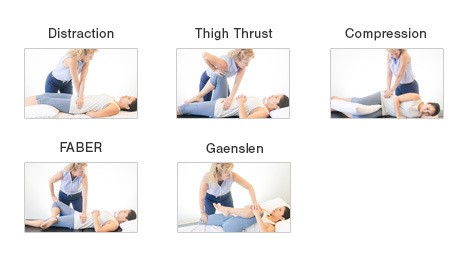

A number of provocative tests to elicit pain have been described, which have been reported to have variable sensitivity and specificity. However, when three or more tests are found to be positive, the probability of the diagnosis is up to 93% for sacroiliac pathology.

si-bone.com

si-bone.com

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction tests.

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging studies are used to aid in the diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction/instability, and also to rule out any other potential reasons for pain.

Plain X-rays are initially obtained of the pelvis, and A/Prof Woodgate prefers to have a full series of functional views. This includes so-called “flamingo” weightbearing views (where an X-ray of the whole pelvis is taken when standing on one leg and a separate view standing on the opposite leg), inlet and outlet views of the pelvis, and oblique views (which are taken looking down the line of the sacroiliac joint). The advantage of the weight-bearing flamingo views is that they may clearly demonstrate instability, particularly noted anteriorly at the pubic symphysis. If lumbar or hip pathology is suspected based on the history and examination, X-rays of these areas will also be ordered as required.

Following review of the plain X-rays, further imaging studies are occasionally used, including bone scans (with SPECT imaging to isolate specific pelvic and lumbar areas of inflammation). MRI scans of the sacroiliac joints have not usually been found to be of great benefit, but if lumbar or hip pathology is suspected as a possible cause, MRI scans of the lumbar spine or hip are arranged as necessary. CT scans are also sometimes obtained and may better show erosive changes in the sacroiliac joints, especially if the underlying diagnosis is related to an inflammatory arthritis (spondyloarthropathy) such as ankylosing spondylitis.

DIAGNOSTIC INJECTIONS

Due to the lack of reliable clinical and radiological studies to diagnose sacroiliac dysfunction, it is helpful to utilise a diagnostic sacroiliac injection (with contrast enhancement arthrogram to confirm localisation within the main synovial part of the sacroiliac joint). This injection is usually performed by the interventional radiologist using CT scan guidance or fluoroscopy (Xray), and involves the injection of local anaesthetic, often with added steroid. A repeat diagnostic injection will occasionally be used if there is doubt about the positioning or technique used for the initial injection. The average volume of the sacroiliac joint is reported to be 1.08ml (with a range 0.8-2.5ml). Approximately 2ml of injection fluid is typically used, and excessive amounts may leak through any deficiencies in the anterior or posterior capsule.

The response to a diagnostic injection is recorded on a pain chart that is filled in by the patient. A usual positive response will show significant decrease (often 75% or more) in pain score immediately after the injection, which will likely last for 4-6 hours due to the effect of the local anaesthetic, followed by a rebound back to the pre-injection level. Over the following 5-10 days, there is often a second period of improvement due to the effect of the cortisone (steroid) injected at the same time. A/Prof Woodgate refers to this as a “double-bubble” response. It is thought to reflect a combination of both mechanical and inflammatory components to the sacroiliac dysfunction. If only the initial dramatic response is seen due to the local anaesthetic effect, it implies a predominantly mechanical cause only.

Some patients will rarely show virtually no response to a diagnostic injection, despite having what would be considered as a typical history, clinical examination and imaging studies. This is considered to be related to either a technically inadequate injection, overwhelming chronic pain, or referred pain from another area (the opposite sacroiliac joint, the lumbar spine, or the hip).

SUMMARY

Once the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint dysfunction is confirmed, based on history, physical examination, imaging studies, and aided by diagnostic injection, a definitive treatment plan can then be individualised for each patient, typically staring with conservative (non-surgical) management, and should there be a failure of response, surgery options may be considered.