Introduction

-

Acute low back pain:

- Defined as low back pain lasting up to 12 weeks

- Most common between ages 35 to 55 years

- 60 to 70% severe enough to require work absence return to work within 6 weeks; 80% to 90% return within 12 weeks

- 70 to 90% of patients will have improvement in back pain within 1st month after onset regardless of treatment

- Recurrence 20 to 72%

- Chronic low back pain:

- Definition

- Low back pain lasting longer than 12 weeks; or

- Frequently recurring low back pain; or

- Pain lasting beyond normal healing period for a low back injury

- Chronic symptoms develop from an acute episode in 5 to 10%

- Definition

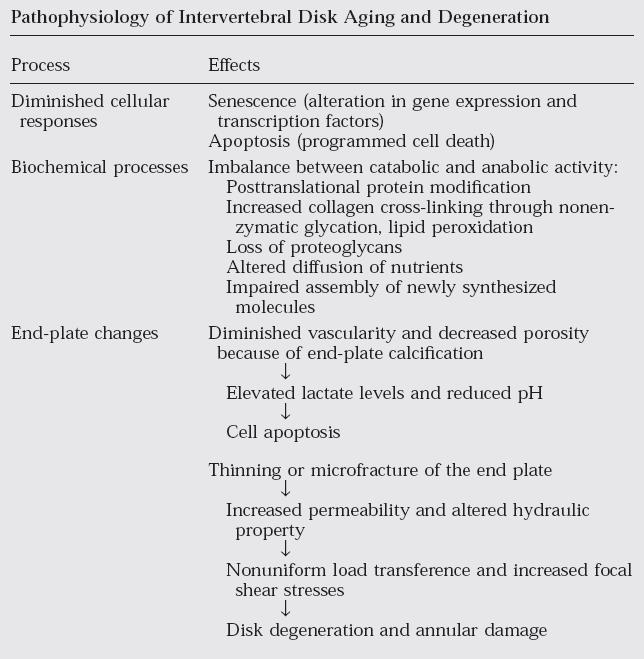

- Pathophysiology:

- Clinical manifestations:

- Symptoms usually develop subsequent to an accident or incident, but often onset is insidious

- Pain typically increases with activity & decreases with rest

- Imaging:

- Demonstrate either no abnormalities or varying degrees of degenerative changes, which often are those that are expected as part of normal aging

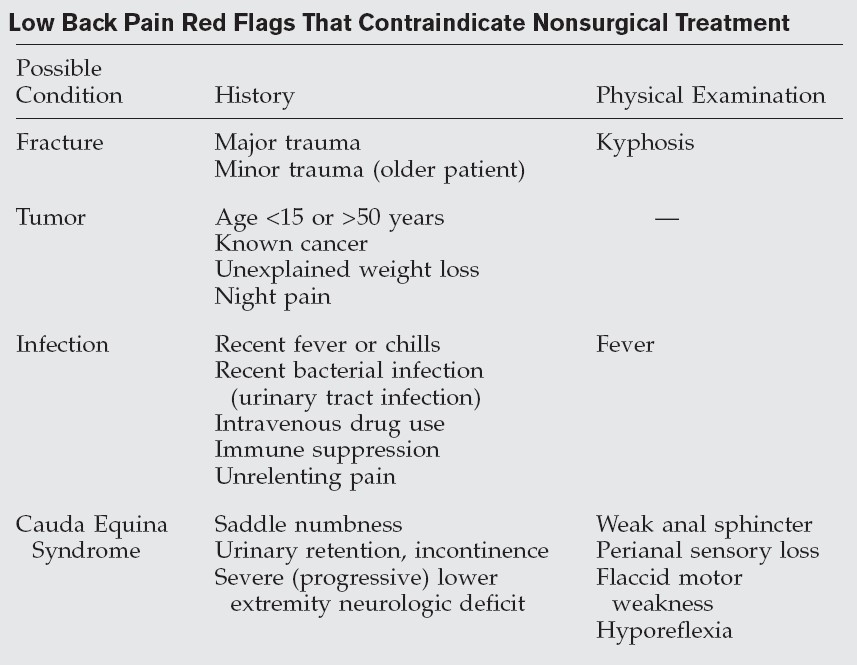

- Disorders of cauda equina &/or lumbar nerve roots:

- Distinguished from more common type of back pain by the presence of radicular symptoms with or without neurologic changes

- Non-musculoskeletal aetiology of low back pain:

- Renal

- Calculi

- Infection

- Tumour

- Vascular

- AAA

- Renal

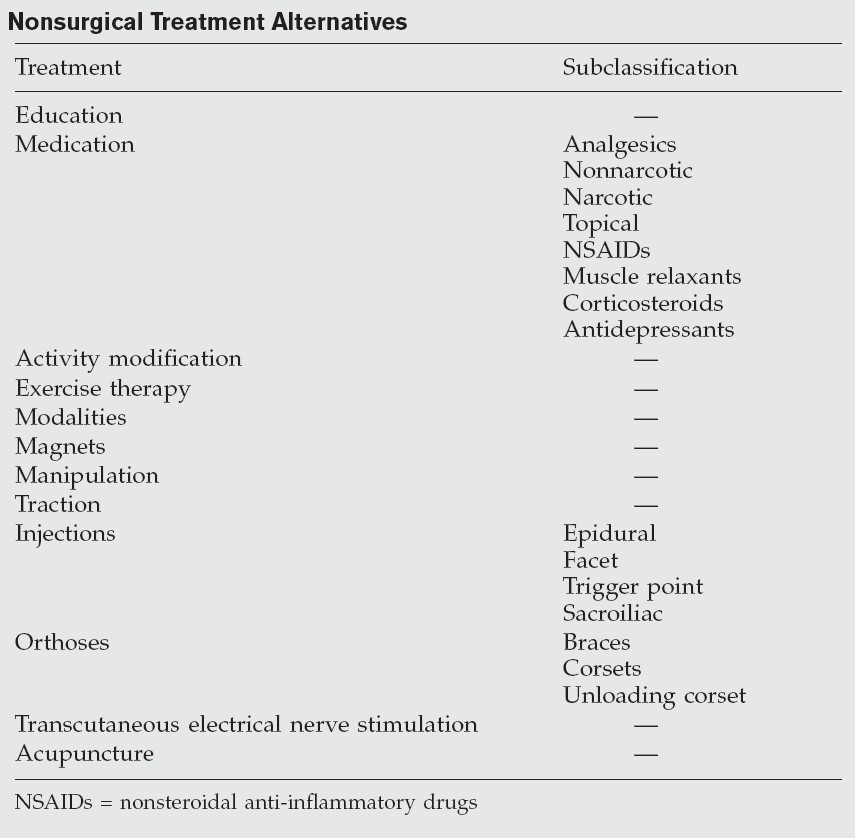

Non-operative Management

- Education:

- Expected outcome & favourable natural history of low back pain

- Assist them to become active participants in their own treatment

- Correct posture & lifelong commitment

- Prevention of dependence on medication

- Medication:

- Non-narcotic analgesics

- Acetaminophen (paracetamol)

- ® Mild to moderate pain

- Highest dose in adults is 4 g/day

- Prolonged high-doses can result in severe or fatal hepatotoxicity (LFTs if taken for > several months)

- ® Should be avoided in patients who abuse alcohol or have a known hereditary liver disease

- Tramadol

- ® Centrally acting analgesic chemically unrelated to opiates

- Weak effect on monoamine oxidase receptors in spinal cord & competes with narcotics; thus, tramadol should not be used concurrently with opioids

- Should be used cautiously in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors because tramadol inhibits noradrenaline & serotonin uptake

- Dosage reduction recommended in patients with impaired hepatic or renal function & in persons > 75 years

- Short-term use recommended & reserved for patients with severe pain

- Acetaminophen (paracetamol)

- Narcotic analgesics

- Only in patients whose pain is unresponsive to appropriately prescribed alternative medications or when other analgesics are contraindicated

- Short-term

- Topical analgesics

- Capsaicin induces & depletes substance P from sensory C-afferent nociceptive nerve fibres

- May be useful for mild pain

- NSAIDs

- Inhibit synthesis of enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), thus inhibiting synthesis of prostaglandins

- Celecoxib (Celebrex) decreased gastrointestinal side effects due to selective action on COX-2

- Muscle relaxants

- Short-term management of acute back pain

- Side effects include abuse potential, dependence, withdrawal when abruptly discontinued, drowsiness, & dizziness (later 2 may be reduced by night-time administration)

- Oral corticosteroids

- Short-term use in patients with radiculopathy

- Potential for severe side effects associated with either long-term use or with short-term use in high doses (>60 mg) limits use as a first-line agent & precludes use with chronic low back pain

- Antidepressants

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline)

- Neurogenic pain, in particular chronic back pain & chronic pain syndromes

- Sleep disturbance is not uncommon in patients with chronic low back pain & is often related to depression

- Sedative properties & therefore recommended for night-time use

- Neuropathic modification

- Pregabalin (Lyrica) and Gabapentin

- Non-narcotic analgesics

- Activity modification:

- Bed rest for maximum of 48 hours following an acute episode

- Painful activities should be avoided for at least a few days until more acute symptoms decrease then encouraged to remain physically active

- Fear-avoidance beliefs about work & physical activity (i.e. avoidance of work & activities because of fear of increased symptoms) are strongly related to disability caused by back pain

- Passive physical therapy:

- Cold packs

- Cold provides pain relief & reduces inflammatory response by vasoconstriction following an acute injury

- Heat packs

- Heat relaxes muscles, improves tolerance to exercise, & may be a reasonable modality when acute phase is over (after 1 to 2 weeks)

- Massage therapy

- Subacute & chronic back pain

- Cold packs

- Exercise therapy:

- Low-impact cardiovascular & aerobic exercises provide other benefits, such as improved mood, increased pain tolerance, & prevention of deconditioning

- Low-stress aerobic exercises can be started during 1st 2 weeks after onset of low back pain symptoms

- Trunk stabilisation & muscle strengthening exercises useful for chronic low back pain, restoring normal lumbosacral motion & emphasise correct body mechanics & posture

- Reduce risk of bone demineralisation & associated fragility fractures

- Magnets:

- No benefit demonstrated in controlled trials

- Manipulation:

- Include chiropractic & osteopathic modalities (no strong supportive data)

- May reduce symptoms in 1st 6 weeks

- Should be discontinued & patients reassessed when symptoms persist or when there is evidence of radicular neurologic symptoms

- Once acute episode resolved, no evidence supports practice of maintenance treatments

- Severe or progressive neurologic deficits are contraindications to manipulation

- Traction:

- No high-quality RCTs demonstrate a benefit

- May be generally associated with a greater morbidity, especially in elderly

- Injections:

- Epidural corticosteroids

- Interlaminar, caudal, & transforaminal methods

- Fluoroscopy to reduce complications & misplacement

- Effective in patients with radiculopathy

- No evidence that they are effective for acute low back pain

- Strong evidence for use in chronic low back pain

- Complications include dural puncture, spinal cord injury, epidural haematoma, abscess formation, & nerve damage

- Limited to no more than 3 in a 6-12 month period

- Not appropriate when there is no indication of radicular nerve–related symptoms

- Facet joint

- Facet joint osteoarthritis

- No evidence supports use in management of acute low back pain, however may provide short-term functional improvement in patients with chronic low back pain

- Intra-articular, medial branch blocks & medial branch neurolysis

- Facet joints are richly innervated by branches from posterior primary rami

- Denervation needs to consider direct, local, & ascending facet branches

- Overlapping nature of innervation means that to denervate 1 segment effectively, 3 levels may have to be approached

- Radiofrequency neurotomy (rhizolysis) has also been found to provide short-term relief of chronic low back pain

- ® Should be considered only after multiple facet blocks have been performed

- Trigger point

- May be useful in back pain secondary to myofascial syndrome

- Sacroiliac joint

- Diagnostic, to exclude alternative source of pain – 15-30% of back pain reported to originate from sacroiliac joint

- Prolotherapy

- Involves injections with sclerosing agents into ligaments of back & pelvis

- No scientific evidence supporting its efficacy in facet disease – some good reports with sacroiliac pathology

- Epidural corticosteroids

- Orthoses:

- No direct evidence however may act as proprioceptive reminders to use correct spine mechanics during lifting & bending activities

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS):

- Short-term relief

- Acupuncture:

- Literature demonstrates mixed results

- Behavioural therapy:

- Includes cognitive behavioural therapy

- Enhance treatment by addressing cognitive (negative emotions & thoughts) & behavioural (altered activity & medication dependence) aspects of chronic pain